Reduce your Inputs

To feel more, let in less

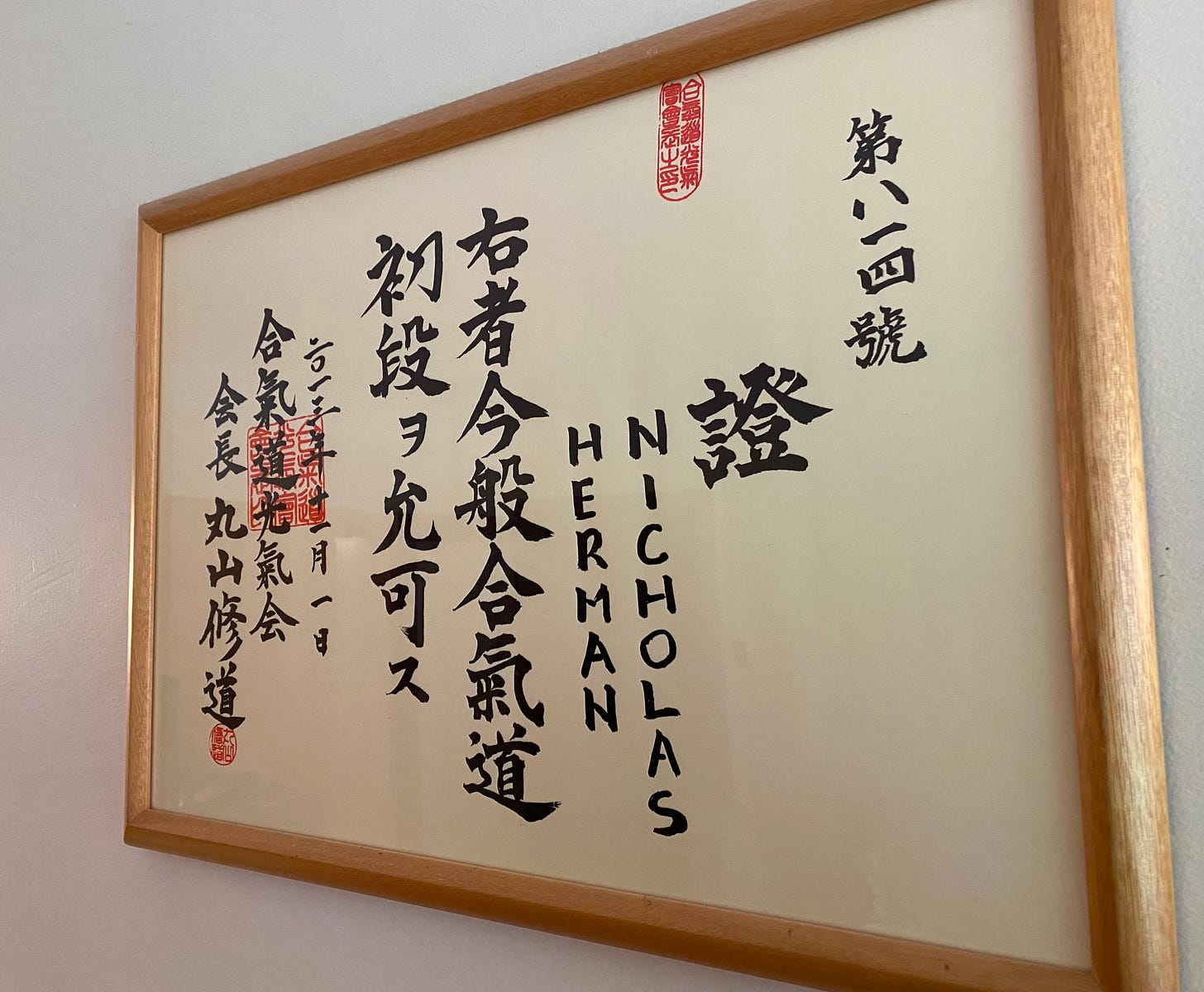

Around 2013, shortly after I had made shodan1 in Kokikai Aikido, we had a guest instructor in our dojo. Like a sudden gust of wind, the 6th dan Japanese physicist arrived one Saturday morning, while on a visit to San Francisco from Boston. He was flanked by a couple of admiring middle-aged women. Like many Japanese people born in the 1940s and 50s2 he gave off a bit of a countercultural vibe, and had his grey hair in a ponytail.

In this class, he gave some advice I keep coming back to, more than a decade later: Reduce your inputs.

You could also simply say: “do” less. Or maybe, “let in” less. Language is tricky. By this, I mean not just through quantity of actions, but in a spatiotemporal sense, moment to moment, throughout your entire being. This has deep implications for the way we move, think, and live.

Most people in North America, and to some extent, the developed world, are drowning in maximalism. Writing about the excesses of technology and social media is currently in vogue, but it’s merely the latest example of what happens when an excess of capitalism replaces real life. Stress multiplies and communities die. This seems to me part of why, particularly in Anglo countries, people seem hyper stimulated, yet often depressed and alienated from one another.3

On the one hand, North Americans (and arguably the British) lack both the strong social welfare systems present in much of Europe, as well as the the root communal and familial bonds still present in much of the so-called developing world. So we’re getting the worst of both worlds. Is it any wonder the (mostly American) internet has become a repository of (increasingly AI-filled) depression, hyper-spastic doom slinging and empty “content”?

In places where people still have strong communities and bonds, these forces are less insidious—because they haven’t let them in to the same degree. In Germany, this is accomplished partially through legislation, while in Mexico, it’s through the force of pre-existing priorities, and thousands of years of being part of the land. As I previously wrote in my entry about Mexico City, in a quote that resonated with multiple people:

..in Mexico, despite child poverty, corruption, and non-potable water, life is still for living, and enjoying—this is the message I got.

Don’t get me wrong—life in one of the world’s largest metropolises can be very excessive, noisy, chaotic, polluted, and crowded—and yet, people still often seemed to me to be more joyful and less stressed than in many richer places.

So if we’re lacking in alternatives, what can we do? If not for my 20+ year practice of aikido, zen, meditation, and other such fancy word stuff, I would be a much more messed up person. We are what we eat. This is where active relaxation comes in, of which a reduction of inputs is one facet.

Koichi Tohei, one of the top students of the founder of aikido, Morihei Ueshiba, and one of the people most responsible for spreading the art, once famously said,

“The only thing of true value he taught was how to relax....Even the relaxation Ueshiba Sensei taught was not explained in words, but rather something he demonstrated with his body.”4

How do you relax while still being in control? By maximizing your efficiency—not in accomplishing tasks, externally (though doing so will ultimately aid in that), but internally, through the way you use your muscles, fascia, neurons, mind, body, and whatever other conceptions we can invent. Reducing your inputs, or stimulants, is a great way to facilitate this process (just ask the dumbphone crowd).

One of the implicit principles of the so-called “internal” martial arts, of which aikido is one (along with the Chinese trifecta of Tai Chi, Xing Yi, and Ba Gua)5, is that you sense more when you do things more delicately and softly. This is counter intuitive to most peoples’ ideas of self defence, and more generally, of external success and power. Paradoxically, I’ve found that being in a relaxed but alert flow state allows me to generate more focus, power, and creativity, with less effort.6

A few years back I attended a seminar with a top teacher in Seattle. One of my practice partners throughout the weekend was a local guy, sturdy, with a grizzled grey beard and faded jeans, probably 20 years older than me. He seemed to be no stranger to manual labor, and probably had some of what Ellis Amdur7 has called, “farmer’s strength.” He had only been practicing aikido a few years.

During a break on Sunday, I was outside, observing the current boomtown of Seattle real estate, when I saw him back in his street clothes, heading out. We chatted for a minute, and he said he needed to leave early. Then, in a matter of fact tone, he looked me in the eye and said, with gratitude,

“You are very gentle. It's easy to be rough, but it's hard to be gentle with someone like me.”

This warmed my heart. I would argue that you can only be both gentle and effective, or both soft and powerful, when you’ve learned how to reduce your inputs. This is also what I’ve learned from Dan Harden, who is able to do this at a level that’s far beyond nearly everyone. Animals do this naturally—try to move my 10 pound cat that’s been lounging on her favorite cushion, and see how well it goes for you. (The author is not liable for ruptured hands or torn clothing).

I once did some friendly sparring and martial-sharing with a buff, 200-pound, skilled kareteka, in a local park. He was from Guadalajara, Mexico, and had actually pragmatically used his skills—he showed me the scar on his face from the time he fended off a knife-wielding assailant and his attack dog.

I’m about 150 pounds. Karate can be very effective (clearly!) but is generally thought of as a highly “external” art. To demonstrate what I was all about, I invited him to put our hands on each other, Tai Chi style, and asked him to try and move me. He immediately pushed me with full force, but could only budge me with great effort, in stops and starts, a few inches at a time. This shocked him.

After a bit of this, I attempted to explain some of the internal logic behind these sometimes mystifying demonstrations.

“I have never heard this before,” he admitted.

That’s also usually the case with our internal worlds. Extra effort and additive stimulation are seen as a net good, even though virtually all biological systems are highly nonlinear. When stressed or busy, rather than doubling down on action, it’s usually better to step away, focus on less, and let your mind fill in the gaps—slowly—between a cloud, a cup of tea, or a stranger’s laugh. I believe, but can’t fully prove, that this is also part of why we literally can't learn or make new memories well without proper sleep.

Skilled artists often understand these ideas intuitively, because effective art has a way of piercing the soul in ways words and “content,” usually can’t. For instance, one of my most enduring musical influences, Boards of Canada, are geniuses at tapping into the subtle yet piercing frequencies that captivate and slow the perception of spacetime. The reclusive Scottish brothers have made a career out of knowing exactly how much (or how little) to change their melodies and textures, for maximum emotional effect.

If your life is sad enough to not already be familiar with BoC’s particular brand of sonic magic, find yourself a quiet hour (preferably in the late afternoon or evening) to lie down on your carpet, wooden floor, grass, or yurt, and listen to Music Has the Right to Children, a perfect 10 on Pitchfork.

Zen master, Shunryu Suzuki once said something like (and I’m going from memory here),

“the reason I have you all sit the same way (on meditation cushions), wearing the same clothes (robe/monk’s outfit, uniform, etc.), is so I can see your true nature.”

Much like a science experiment, if we change or add too many things in our lives, too quickly, we spoil the soup. Reducing inputs is a necessary precaution when our wild and intuitive natures have been hijacked. It’s also my first line of defence when I feel overwhelmed, tired, or stressed. I think: what’s actually essential, right now?

To use a lurid example from the extremes of consumerism, modern porn is usually the opposite of real love or sex. Through its excesses and attempts to stimulate maximally, it bears very little relation to the actual experience of slowly caressing and being intimate with another person, square by square, moment to moment, within the totality of our lives. (20-somethings—you’ll understand when you’re older).

You can slowly drink a cup of tea, or guzzle an energy drink. True, they both have caffeine (and other stimulants), but the way and rate at which we experience them have very little in common with one another.

To feel more, and express more deeply—emotions, intentions, power, and clarity, reduce your inputs. It’s the same reason why it’s a good idea to breathe in less air8, meditate, and occasionally fast. Then add inputs—gradually and slowly.

Back when I lived in my $625/month room in a crumbling Victorian house in San Francisco in 2008, I had a quote printed out above my bed, by Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh:

“To spend one hour drinking a cup of tea is an act of resistance.”

The rain is falling hard right now, but next weekend, for my 40th birthday, I plan to see my friend Bill in Port Townsend, and then backpack a couple nights in Olympic National Park with my partner. Being in a true wilderness is pretty much the original noise reduction, and there will be plenty of time for slow tea, and watching the flames of my MSR PocketRocket cook what fits into a bear canister. But I’m still going to spend an hour (or more) on tea, today.

First degree black belt.

A few well known 70-something Japanese dudes include: Haruki Marukami, Ryuichi Sakamoto (+ the whole YMO crew), and Shigesato Itoi.

For a fascinating comparison, visit Montreal—while still in North America, the energy of locals—who talk to strangers on the street, without pretense, and manage to dance and socialize in parks without being glued to their apps quite so much, is very different from the rest of the continent.

Source: Aikido Journal

I’ve studied Tai Chi with a couple teachers, and sparred with people 6 hours a week, while learning Wing Chun when I lived in Taipei. I’ve also had some exposure to Ba Gua and Xing Yi. There are many things practitioners of the Japanese arts can learn from these approaches, and I highly recommend them.

My longtime practice of Gong Fu Cha (功夫茶), making and drinking tea, also aids me in this, and is one of the best things I got out of living in Taiwan, but that’s a post for another time.

Ellis is a famed instructor of classical Japanese martial arts (Koryu), a mental health specialist, and a great writer. I highly recommend his books, especially, Dueling with O-sensei: Grappling with the Myth of the Warrior Sage.

I previously wrote about some of these ideas while backpacking through a rainforest and up to a glacier.

Happy Birthday! Sounds like you have some amazing plans for celebrating it. I can never think of anything I want to do.

I'm definitely not a meditative type, but I used to hike up a nearby mountain every Sunday. I did this for a long stretch while I was writing my novel, and I think what made me do the same hike every time was knowing it would exhaust me (the last mile is a pretty intense climb) and that on the way back down when I was super exhausted, that's when new ideas would come to me.

Anyway, that's what it takes to get my chattering mind to shut up and let something new in.

Very timely post Nic —reducing inputs, like having emptyish spaces seems to be something I can always shave down more and more — and ditto on the happy birthday wishes this coming weekend, sounds like a solid plan to kick off the 40s. I had my first ever martial arts class—aikido as well—about 10 days ago —and I will be going back. Keen to read more about that and your Taiwan gongfucha story that you mentioned will be a subject of another post. Excited for it when it the time comes.