Santa was ascending the stairs, so I said buenos noches to him.

“Buenos noches,” he replied back, looking tired.

Regular Santa has a magic sleigh, but this hard working chilango Santa still had to climb three flights of stairs above a carpark after his work was done.

We were on our way out of our semi-faded airbnb apartment for a nightly walk when we saw him. It was about 6 days before Christmas. Rounding the corners of our modest Escandón neighborhood and riding the sidewalks up and down, which are pushed up by huge tree roots (one of the main occupational hazards of this megalopolis), cheap lights were strung up festively, and small doorways revealed hidden portals into the labyrinthine and often deceptive metropolis known as Ciudad de México, or Mexico City.

Often known, confusingly, simply as México within the country by the same name, it is the oldest capital city in the Americas, and one of only two founded by indigenous peoples. It is also built on a drained lake, at an altitude of 2200 meters, in a valley of snowy volcanoes. This partially explains the sidewalks—the entire city is slowly sinking into volcanic soil—which has the unfortunate consequence of causing buildings, sidewalks, and small dogs to become gradually tilted, like al pastor tacos unraveling under the weight of their own porky heft.

As we passed one low-rise building, the doorway revealed an extremely old and small woman clapping frenetically and calling out incantations to her elderly flock, from inside a a sort of church stuffed in a shoebox. Continuing down the street, we heard loud horns coming from behind huge and imposing doors. A small and ebullient watermelon-shaped lady welcomed us in. It was filled to the brim with young, hip locals, and a band was playing.

My partner, Cathy, who speaks much better Spanish than me, conferred with her to find out what it was all about. After a few minutes of conversation I attempted to follow, I asked Cathy what she had learned.

“I have no idea what she’s saying,” she admitted, “I don’t think she’s used to talking to non-Mexicans.”

Just then, a bearded young musician who was getting ready, came over and said,

“I speak some English. I can explain!”

He told us that this party was part of a benefit event in light of the recent destruction that Acapulco hurricanes had brought. More importantly, it was also part of the tradition of posadas, a 9-night celebration leading up to Christmas, which includes bible plays, as well as celebrations and piñata smacking, with different families often taking turns hosting parties

These types of traditions used to be popular in medieval Europe, a way for the church to teach morality tales to a largely illiterate population. They eventually fell out of favor, but found new life in Mexico—like so many things, through syncretism—it coincided well with an Aztec solstice festival called Panquetzaliztli, which involved the ritual sacrifice of human prisoners and the consumption of Amaranth. The Spanish later outlawed the growing of amaranth. Ponder that over your next energy bar.

Huitzilopochtli was the god celebrated during the Panquetzaliztli, which derives from the nahuatl words huitzilli (“hummingbird”) and opochtli (“left”—aka, the rising sun). In Mexico, the past is always around you—but you may not know it.

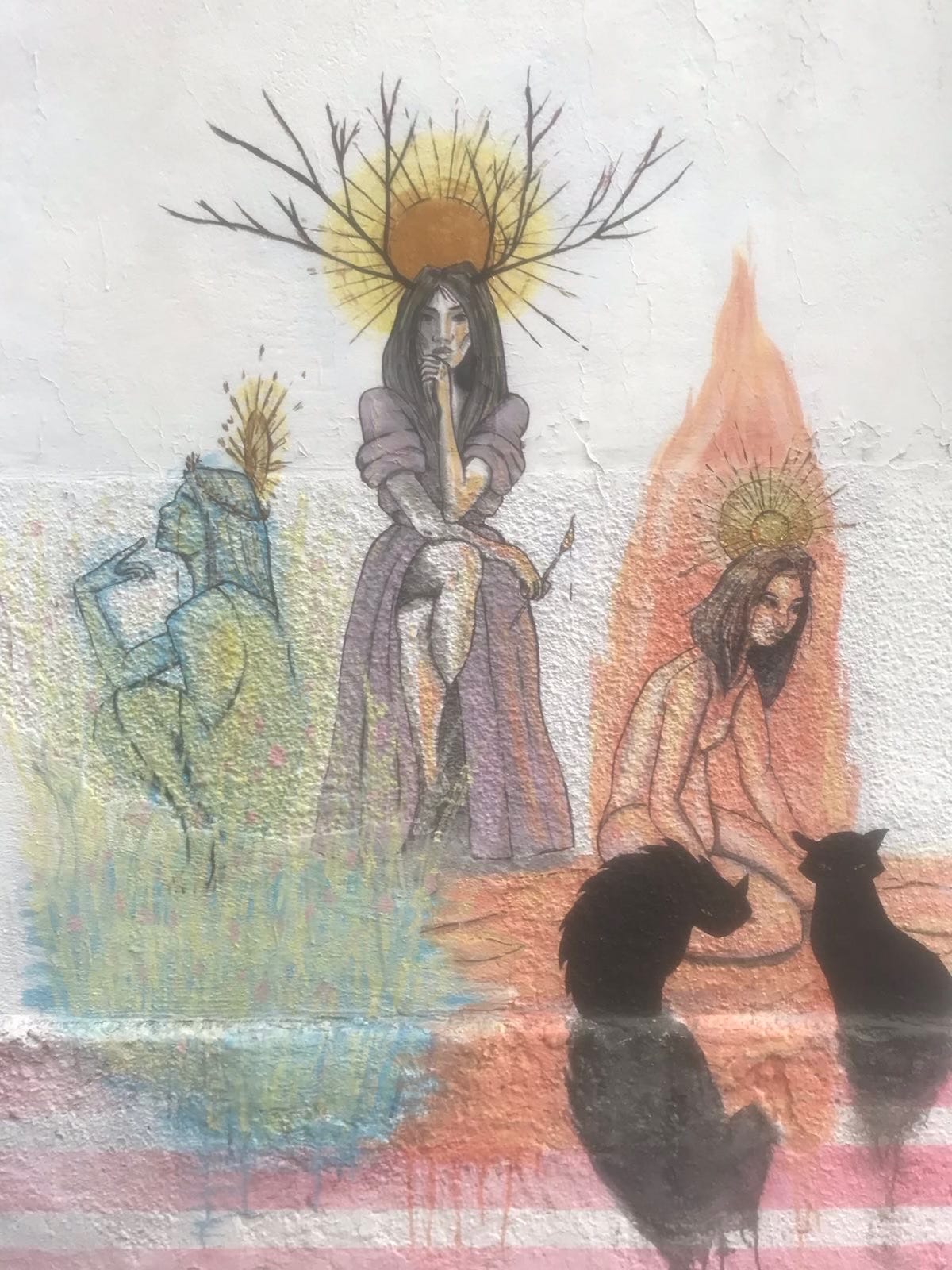

Everywhere you look in this city, there is incredible art work, murals that put museums and festivals in other countries to shame. Surely one reason is this long history of art and festivities linked with the sacred. The Mexican sense of visual artwork is omnipresent and full of vitality, just like the sounds from street vendors, slow burning whistles, the calls for tortillas and buying used machine parts, people gently tapping their feet or girls slowly swaying their hips while waiting in line to buy sweet corn—movement.

I sometimes had the feeling of being in a labyrinth of artifacts, as in a medieval city, twisting and turning between the past and the present. Our apartment’s doorman buzzed people in and out in a tiny room with a degraded SNK vs Capcom video game poster, and sat in a plush chair covered in a giant peeling Union Jack. The streets were littered with open-air shops of every kind, not only for eating, but also for shoe repair, clothes sellers, laundry, electronics, funeral caskets, beds, and many other things that disappeared from view in “the rich world” as life became more packaged and private.

One day I walked through the leafy colonial streets of Condesa to find an English language bookstore in the former building of an art deco American Foreign Legion, above a noir bar—the curt woman working there said the owner travels all around America buying books to bring back to the store.

“He hates it,” she flatly said.

Walking through these tree lined streets and into the even more chic (slash-gentrified) neighborhood of Roma, past countless small outdoor restaurants, cafes, and bakeries, you can almost imagine you’re in Berlin, or another bohemian European city. The main streets of the city are massive, but the many side streets and alleyways make life more livable and pedestrian friendly, as in the countless alleyways of Tokyo, another similarly sized metropolis at the other end of the cultural spectrum.

As I ate a creamy dulce de leche paleta (a kind of natural popsicle), I lingered in the wide-open parks where couples languidly embraced each other on benches, people worked out, and families played or spun around on scooters and roller blades. Somehow, despite being a gigantic mega city known for pollution and inequality, the quality of life and abundance of public spaces is still far more relaxed and amenable than most places in North America.

Many aspects of life seem to be preserved in ways that disappeared in America and Canada at least 50 years ago: luxurious full service cafes, ice cream parlours (also full service) with men in tuxedos, restaurants where no one will ever tell you to leave or “just come by to ask how you’re doing” (but actually wanting to move you along), because in Mexico, despite child poverty, corruption, and non-potable water, life is still for living, and enjoying—this is the message I got.

One day I visited the Museum of National Anthropology, one of the most comprehensive natural history museums in the world. The collection of ancient objects, intricate stone carvings, bizarre masks, and kaleidoscopic iconography spanned thousands of years of Meso-American history, and outdid the most fantastical video game and graphic novel designs I’ve ever seen. I started to see where the heritage of wildly creative and explosive sense of visual art came from.

Through the exhibits, which include representations from the Olmec, Toltec, Aztec, and Mayan civilizations, as well as even more ancient nomadic hunter-gatherer societies, there are common threads of agricultural gods and omens, and the importance of shamanism and art, which also occur in ancient Egyptian and Chinese societies.

In all these societies, blood was a sacred link to the holy world, and both kings and priests shed it, through auto-sacrifice and rituals of bloodletting, as well as the more well known whole sacrifice of warriors and prisoners. The spiritual world seemed to be, as my friend Bill Porter/Red Pine once said, “the real world,” in large part. One rare English plaque in the Mayan wing emphasized this point:

“In all classes of life in Mayan society, rituals suffused daily life.”

Rituals, of course, that were embedded with the sacred, the artistic, and the communal; in contrast to the mundane, consumeristic, and isolating worlds many of us find ourselves in the present.

Outside the museum, which is located in one of the richest neighborhoods of the 5th largest city in the world, handwritten notices were taped to the entrance of the slick glass sliding doors. More syncretism in action.

Some type of indigenous acrobats were twirling and spinning upside down from a great height around a structure, while vendors sold trinkets and food nearby.

There is plenty of variety. Go to the mercados and buy your produce. Idle around Polanco and observe the Mexican (and Russian) super rich, or experience the improvised economy at a swap meet at Tacubaya metro station, where you can take a train that goes through the entire city for 5 pesos, or about 29 American cents as of this writing. The stations can be a bit grimy, and the trains can get pretty crowded, but everyone can afford it—to go the same distance by taxi might cost 200-400 pesos, depending on the distance and time of day. This differential is staggering.

If you decide to hop a taxi, you can enjoy the infamous D.F. congestion, idling past cramped minibuses with multicolored faded signs showing nearly unpronounceable destinations (AZCAPOTZALCO) as the driver’s helper sticks wads of bills between his knuckles and his arm hangs out the window. Meanwhile, at the light, a woman on a 4-foot tall unicycle starts to juggle hoops, a man walks between the cars selling candy, and another man furiously starts washing the windows of a truck, all hoping to make a few coins before the next green.

This is also Mexico City, a place with crystal chandelier department stores, little 15 peso taco stand stalls on street corners open late into the night, where hand milled corn can occasionally be found beaten out violently by a powerful young woman slaving over a giant metate, where you can watch the latest Aki Kaurismaki film in a chic cinema bar, and buy some of the best and strongest cacao in the world.

Layer beyond layer of history, walk through the cobblestone streets of Coyoacán, which Cortes made his base, where he was treated as a god—and which he then decimated. Spanish churches and old squares more lovely and cathedrals older than anything in Boston, rivaling London, alongside people performing Aztec incense-covered smoke ceremonies and community indigenous dances late at night, the shadow of ancient pyramids built in the distance, we don’t know by whom (but the Aztecs claimed it and decided to camp out there), a short but maddening-traffic filled ride away. A layer of smog for you to escape from, fanning out to the rest of the country.

Drink it all in. Carefully and abundantly.

What a vivid description of the city! You've painted a fascinating picture!

Thanks for the CDMX ride along bruv - hoping a forthcoming post dives deep into cacao - I want to hear all about it 🙌