An interview with writer and translator Bill Porter/Red Pine

Part 3: The Dance of Translation

Continuing Bill’s narrative about his unlikely path into translation, travel writing, why poetry is more important in Chinese culture, and dancing with the dead.

Even though I don't write poetry—never have, never will, probably, but I really like the act of translation, the experience of trying to translate. You deal naturally with words a lot at the beginning, but the longer you start putting things into your language, then you start dealing with something beyond the words. You have this experience of what must have been in the poet's heart when they wrote this poem.

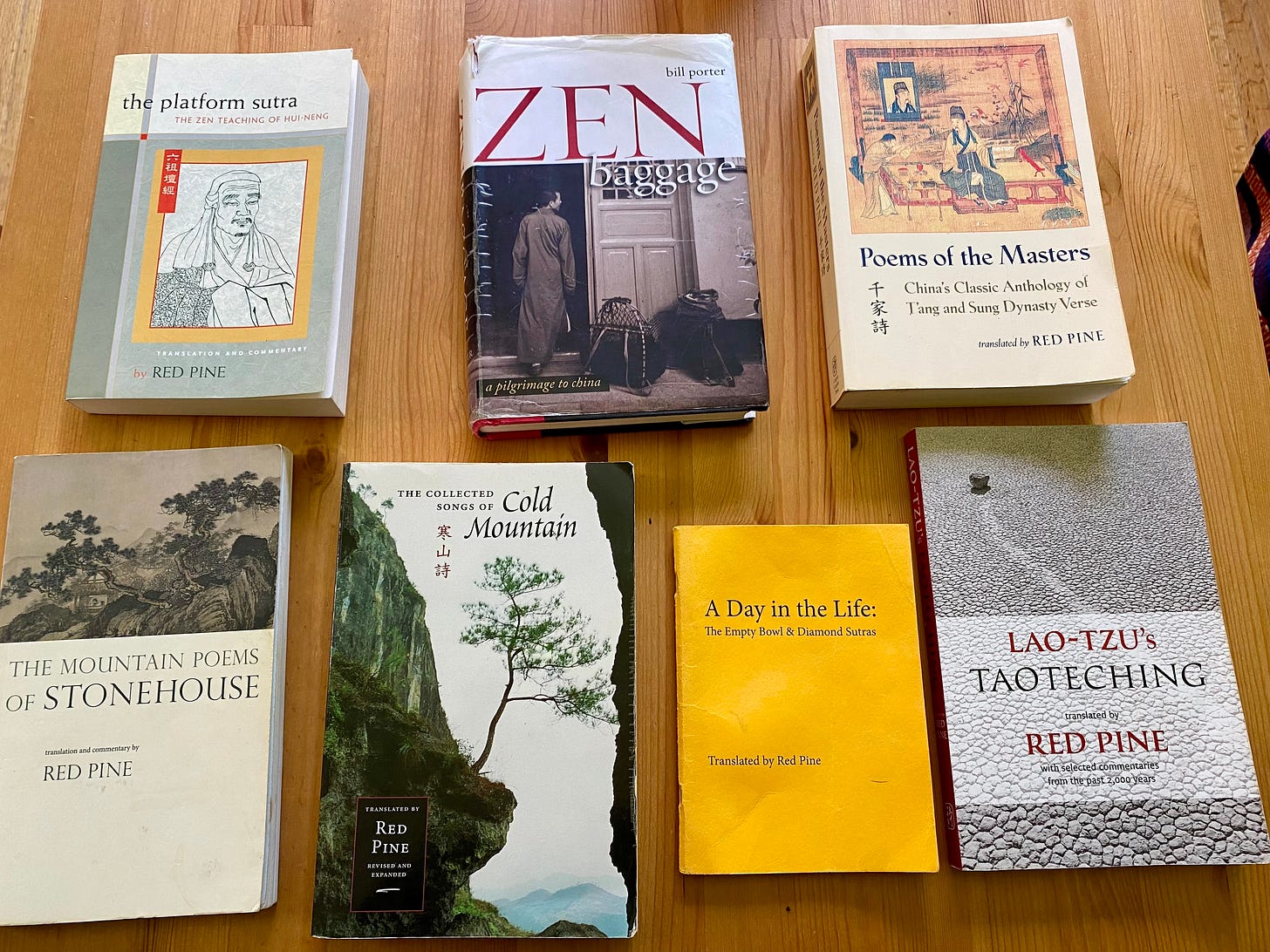

When I was working on Cold Mountain, I'd gone to a bookstore and found this woodblock edition of his poems with other Buddhist poets, and the poet after Cold Mountain was somebody named Stonehouse. I’d never heard of him, and I'd never met anybody who had, but whoever put that book together had, and I'm really glad they did. His poems were even better, I have to say—they were freer and wider ranging and a panache.

Cold Mountain was in your face, just direct, didn’t mess around much, whereas Stonehouse—he messed around a little bit, but without being like some scholarly official with all the illusions of historical events just to impress people. He just wrote a beautiful little Buddhist poem about about the fish swimming in the pond. Anyway, so I kept translating, and I translated all of Stonehouse’s poems too, but now I didn't bother with a publisher.

I decided, I'd met Mike and his friends, and they had their own little press, besides Copper Canyon, called Empty Bowl. They were a bunch of tree planters, many of them poets—so they were storytellers. So I published Stonehouse’s poems with Empty Bowl, and later self-published this book on the Zen teachings of Bodhidharma through them. By then I was sort of hooked on the translation—I never had any idea that I could translate something, especially something profound. I didn't come to Taiwan to translate or even to do any reading—I thought books were for nerds—but here I was translating poetry.

At the time, I still needed a real job, so I worked at a radio station, the old US Army Radio station the US abandoned when we recognized China, and it had become a nonprofit, with a huge listenership in Taiwan. They had heard about me and said,

“Oh, you know Chinese, you can read Chinese, you should do the local news, come in every morning, read the newspapers, and tell us what's going on.”

So I would do all the news and interview people every week. At one point I applied to the Guggenheim Foundation to go to China, to find people like Cold Mountain and Stonehouse and see if people like that still existed. I was interviewing the son of the richest man in Taiwan at one point, that was one of my jobs, Winston Wong, who ran the world's biggest plastics company.

At the end of the interview I asked him if he'd ever seen the movie, The Graduate. He said yeah. So I asked him,

“What would you say to a graduate? Would you say, ‘plastics, plastics son’?”

He said, “no, no, no, I would tell him to follow the Tao.”

So we had a little chat after that. I didn't know he had an interest like that. He was a man with wide-ranging interests. And I said, you know, this is probably the last interview I'm gonna do, because I applied to the Guggenheim Foundation to go to China to find people who were like Cold Mountain and Stonehouse who lived in the mountains and practiced the Dharma.

He said, “wow, that's a great idea! If they don't give you the money, I will.”

So a couple weeks later, I got a rejection letter from the Guggenheim and called up Winston.

He said, “how much money do you need?”

And I said, “I think maybe $4,000 or $5000, or something like that.”

He said, “cash or traveller’s cheques?”

So I called up one of these friends of Mike O’ Connor in Port Townsend, who was a photographer, Steve Johnson, and asked him if he could meet me in Hong Kong in a month. And so, Steve and I went to China together to see if people like Cold Mountain and Stonehouse still existed, people practicing, living in the mountains. And of course, I ended up finding lots of hermits in the Chungnan mountains in Xian. I didn't really intend to write a book about it, but I figured why not, these people are so special. And I did some historical research to give a background, and then just interviewed people with a tape recorder, monks and nuns, Buddhists and Taoists, and wrote this book, Road to Heaven.

It never sold anything in America, but it got me into my first experience with writing, writing prose. I had to quit my job for a year and a half to write that book. While I was wondering what to do after finishing Road to Heaven, my former boss said he was going to Hong Kong to start a new radio station, and asked me if I'd come with him and be his features editor, with the sole job of giving him a two minute feature every day.

I had just called up Winston the week before, and I told him that me and my wife were going to take the kids back to America. We had two kids now, and I told him there was still one thing I wanted to do before I went back to America, and he said well, what's that? I said: I want to explore the origins of Chinese culture by traveling along the Yellow River, and he said, wow, that’s a great idea!

Again, “how much do you need?”

I told him around $9,000, I figure, and it would take about three months to go from the mouth of the Yellow River all the way to the source. The radio station boss said, “that's a great idea for a program!”

So that's what I did for the next two years in Hong Kong. I did all of these travel features where I’d take this trip and then come back to Hong Kong where I would write all these two minute programs.

For each of my trips I would write 240 programs, 240 scripts and so now I learned how to write little vignettes. So, it's funny how you pick up talents or skills. Of course, you have to be receptive to that sort of thing. I was for some reason, I just fell into it. Well, that's how I got into translating and writing, and eventually of course, me and my wife decided, oh, that's enough, and I came back to America and bought this house here where we’re sitting in, in 1993, and been here ever since.

I still travel occasionally to Taiwan. Maybe once every three years. Lately I've been going to China almost every year to work on new projects because I keep running into people and I just want to know more about them. And so I start working on their poetry. It could be people I would have never ever thought of working on, like Wei Yingwu, Liu Tsung-Yuan. But it's also been people like I always wanted to translate like Tao Yuanming, for example. That's sort of my creative life in a nutshell.

Can you talk a little bit about the importance of poetry in Chinese history and culture, and maybe for people who are not initiated into it, what the value or purpose of it coming from a different cultural or historical lens is, to try to appreciate or understand it?

Poetry has always been part of Chinese culture in a way that it never has been in the west. Naturally we've had poets, like Ovid, or Homer, Dante, and poetry has been an art form in the west too—but in China, around the year 600, if you wanted to be an official in China, you were examined on your poetry. It was part of the official exams. Before that, there was this huge anthology of poetry put together by Confucius, called the book of poetry and people would study that too, to impress each other.

That Book of Poetry that Confucius put together has a special usage. It includes poems from all over China at the time, around 500 BC. He compiled it so that his students would know poems from everywhere, because he saw his students becoming ambassadors, working for some king and then going around as their ambassador to negotiate arrangements with other states. So he wanted his students to be able to know poems from every part of China. So that was sort of the function of this book of poetry.

So educated people all studied Confucius's book of poetry, and eventually it became part of the curriculum for anybody who wanted to be an official. You had to write poetry and so the officials started writing poetry to each other apart of their correspondence, instead of writing a letter, which they sometimes did. So poetry has always had a place in Chinese society it never has had in the west and never will. The Chinese have never thought of prose as the greatest literary art, it's always been poetry. Just like painting has never been considered a great graphic art, it’s always been calligraphy. Calligraphy, poetry—those are the great arts—and the reason is they both share the same thing. Both of those arts express the person who practices them. You see someone's calligraphy, you can see what kind of person they are. When you hear their poetry, you know what kind of person they are.

Prose, not so much. You can lie in prose a lot easier, and it's limited by structure, too. There's no loose ends in prose. Even the way the Chinese language works, the grammatical structures are almost the same as in English, whereas in poetry, you never know! Any character can pretty much be any part of speech just about, it's a very creative usages of Chinese language in poetry, you’ll never see that range of usage in prose.

The person who first defined poetry in China in china was Zheng Xuan, around the third century. He made this definition in his commentary to The Book of Poetry. He said,

When what is dearest to your heart is put into language, that is poetry.

Poetry is what comes out of your heart, not your head. It's very different than poetry in the west. We have what we call romantic poetry, but the Chinese are thinking about the heart in a different way, they're thinking about what's deepest in in your heart. This includes, of course, the love for your country, too—we would never think of that as romance, but that's the way the Chinese looked at it. When your highest goals come out in language, that's poetry. And so that opens the door to spiritual poetry, too— the Dharma, Taoist poetry. This aspect of poetry is what attracted me.

I can gain access to a person's heart who lived 2000 years ago by reading their poetry. I could never do that by reading their prose. I could never say I understand this person, all I could say is I understand this man's ideas, if it was prose. But ideas are not the same as heart; ideas don't come from the heart, that's head stuff. The feelings, emotions and something you can't even put into language. So that's what's attracted to me to poetry, and that’s why poetry is so important to the Chinese. When you walk into a Chinese house, the first thing you'll see opposite the door is some calligraphy on the wall, because that's the greatest art, not painting. And what's that calligraphy? It's a poem! Lines from a poem.

Anyways, poetry it’s China’s greatest literary art and it's why the Chinese love it so much and it's why I love it so much too, because it gives you access to a person's heart. As a translator, you have an the opportunity—well, I would say many translators never take this opportunity, because they limit themselves to the words when they translate—but Chinese poetry gives the translator the opportunity to get to know that person who wrote those poems. Become their zhi yin is a term the Chinese use.

A long time ago around a 1000 BC, there was a zither player Yi Boya, who played the qin. The only person who he felt understood his poetry was Zhong Ziqi, this firewood collector. Yi Boya would play a song and then Zhong Ziqi would say, “high mountains, high mountains,” or “flowing water, flowing water.”

This relationship gave rise to the expression, zhi yin, to know someone's tune, to know someone's voice, to hear a person's heart. A translator has the opportunity to become a poet's dream. To discover their voice, to hear high mountains, to hear flowing water in their poetry. And you have to listen, before you know, there's high mountains or flowing water— there may not be the word, water or mountains, or anything like that. But anyway, so that's the idea is a translator has the opportunity to reach someone who lived a thousand years ago and to accompany them in your own language. And that's why I've often told people it's like dancing.

You don't become the other person. English can't become Chinese. That's stupid. And yet, that's what a lot of people think translation is supposed to be and they criticize you for not being, “that's not accurate! That’s not literal!”

Well, if you do that, you're going to kill the dance. But for me, translation is having the opportunity to accompany these great dancers with my dances, as rustic as it may be, because I don't write poetry. I tell people, I would never get on the dance floor by myself, but if you're dancing and if I like the way you're dancing, I would love to dance with you. So that, to me, is what a translator does.

A translator accompanies somebody in their language. And that's why also there's no perfect translation. There's good translation, there's good dancing, and there's bad dancing. The word perfect doesn't make sense. It is what it is. Just like there's no perfect poem. There's also no perfect accompaniment to a poem. But there is good accompaniment. For me, it depends on the way I feel.

But ultimately, it depends upon the audiences. When I publish my translations, whether people like them or not. So that's about the only way you can judge a translator. But the real judgment takes place by the translator themselves on how they enjoyed that experience of getting to know this dance partner. And maybe producing pretty crappy translations, but enjoying it, enjoying the process. For me, that's what it's all about.

I rarely look at the books I publish. Because I could have always danced that dance different today. So I don't want to go over that dance again. But sometimes I do, just for nostalgia. Say, oh yeah, yeah, that was a good dance, I like that! But if I translated that same poem today, it probably wouldn't be the same.

That's why I never memorize any of my translations. Because they can always be different. They can always be better. At least I think better, maybe not. I get older— once mental faculties aren't quite as sharp as they were. But as you translate, you definitely translate things differently.

Nick this is so so so awesome - I could read an entire book of your conversations with Red Pine - enthralling stuff. I saved it for when I had a moment and as I looked out at the harbor from the hospital room with the freshly hatched dragons I couldn’t help but pen a little poetry myself. Too many quotablea to list here but I loved the whole interview.

I will ask again at some point when you’ve got time to give us the map to read Red Pine’s books because I’m nearly ready to dive in.

Great post! It sounds like we're saying the same thing about language—you have to take a leap into the writer's intentions to truly understand the meaning.

Also, so true about literal translation. We had to do that in Greek class as an exercise, and boy did it sound stupid. Not terrible for understanding the grammar, though.

When I was translating Descartes for my senior thesis, one thing that helped me get into the right frame of mind was hearing French philosophy professors talk about how 'modern' he sounded, that his writing sounded as though it could have been written today. I thought that was very strange because every Descartes translation I'd read sounded exactly like what I would expect from a work written in the 1500s. But then again, French always sounds stuffy when you're parsing it in your head. We don't generally say 'whom' anymore, but they do it without batting an eyelash—even some thuggish lowlife on the street will sound like a professor when translated into English. Knowing that made me realize I should just do away with all the stuffy language I was hearing and take some liberties to make it sound the way it does to native French speakers—clear and direct.